We don’t give it much thought nowadays, do we? News and information zip around the world in seconds. People can read about and witness events in far-off places as they happen. This notion struck me while thinking about upgrading to 5G, and again as I was preparing to present music by Alonso Lobo on a recent “Sacred Classics” program.

Lobo was a Spanish composer of the late Renaissance, when Spain was the most powerful nation in Europe. It had many universities, a wealth of great art and music, and an expanding empire. This was Spain’s Golden Age or Siglo de Oro. Miguel de Cervantes produced “El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha,” considered to be the first modern novel and the basis of that high school production of “Man of La Mancha” you saw or even helped stage. El Greco created an expressionistic style of portraiture with elongated figures which I know you’ve seen, including his memorable self-portrait, and religious paintings such as “Opening of the Fifth Seal (The Vision of St. John)” that were truly visionary. Diego Velázquez painted subtle and intriguing portraits such as the famous “Las Meninas,” one of the most debated paintings in history, and later employed the chiaroscuro technique which juxtaposed light and shadow to dramatic effect in breathtaking works such as “Christ Crucified.” This Golden Age also engendered music that is just as vibrant and compelling today. Alonso Lobo would join the company of his elder contemporaries Tomás Luis de Victoria, with whom he worked on editorial projects, and Francisco Guerrero, who was his mentor and one of the preeminent composers of his day.

Let’s remember that this period of history was also marked by a communications revolution, one that was more revolutionary than 5G is today — the printing press. Movable type printing introduced an era of mass communication, and shortly after its advent, music was also being reproduced for the masses in both the lower case and capital “M” case senses of the word.

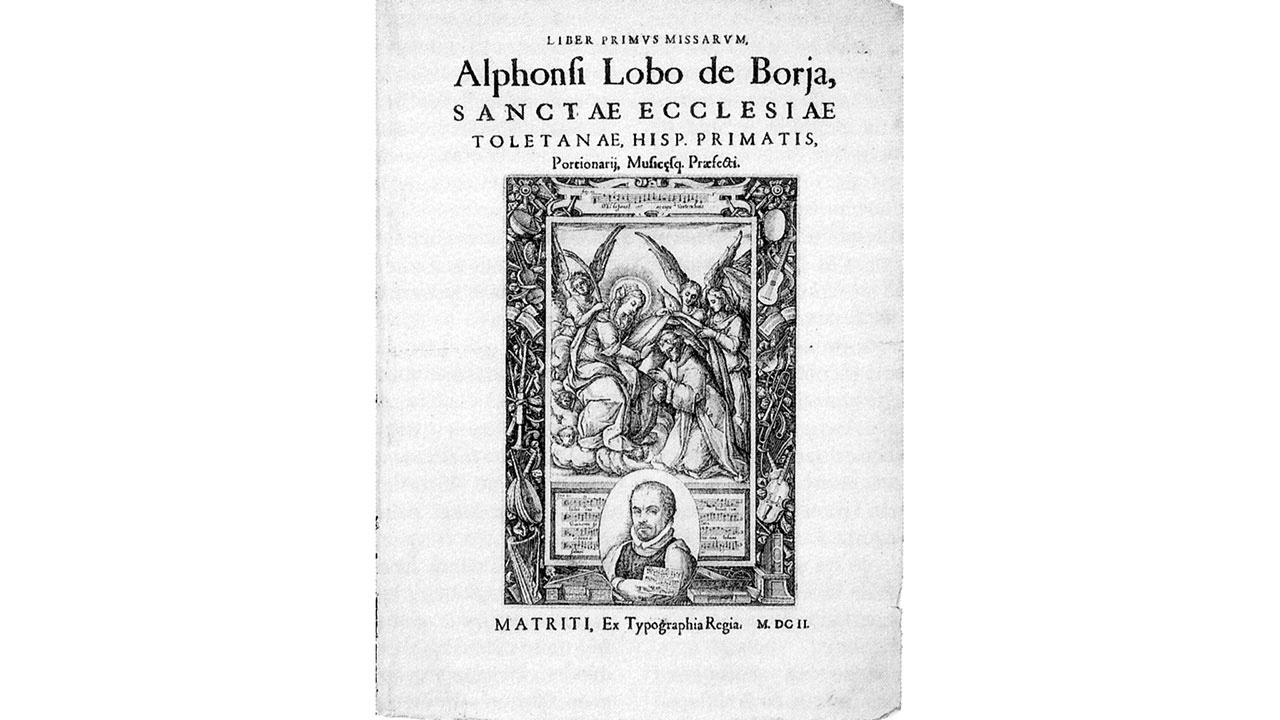

Lobo’s works are Masses and motets, Passion settings, Lamentations, psalms, and hymns. Printing allowed his music to travel far, if not in seconds, to more places in the New World. His “Liber Primus Missarum” was just the third choral collection printed in Madrid, in 1602, under his careful editorial supervision. Five exemplars of the book were discovered in Mexico City, Puebla, Guadalajara, Morelia, and Oaxaca. Until that discovery some 70 years ago, Lobo was virtually overlooked in music literature.

Luckily for you, if you’re a chorister or a choir director, all the Lobo motets in the 1602 publication can now be found in modern performing editions in the Mapa Mundi catalog: “Versa est in luctum,” “Ave Maria,” “Quam pulchri sunt,” “Ave Regina caelorum,” “O quam suavis,” “Credo quod Redemptor,” and “Vivo ego.”

What I found fascinating in researching the works of Lobo, is that Puebla had one of the most extensive early music collections in the Americas. Among the 435 works are Masses, Magnificats, motets, hymns, psalms, Lamentations, and miscellaneous liturgical compositions. By the way, this doesn’t include the music of the 18th and 19th centuries which has works by Haydn, Mozart, and Rossini.

Now, I know what some of you are thinking, and you’re right. We have to acknowledge in this year marking the 500th anniversary of the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, the story of Spanish colonialism, like all of European colonialism, is fraught with difficulties. We can also recognize that the printing press — like social media today — heightened the importance of controlling narratives and manipulating public opinion. Moveable type and tweets are equally conducive to misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda. But, it’s not too late for truth and reconciliation, not at all. The time seems ripe. This is a teaching moment for our children. As many have observed, history is not the past: it is us, and we live with it.

For Hispanic Heritage Month, I thought we might further explore the music of the early Spanish composers Tomás Luis de Victoria, Francisco Guerrero, and Alonso Lobo whose works were among the first to be heard in the Americas and which have staying power to this day — much greater than this blog I zipped off.