No. 21

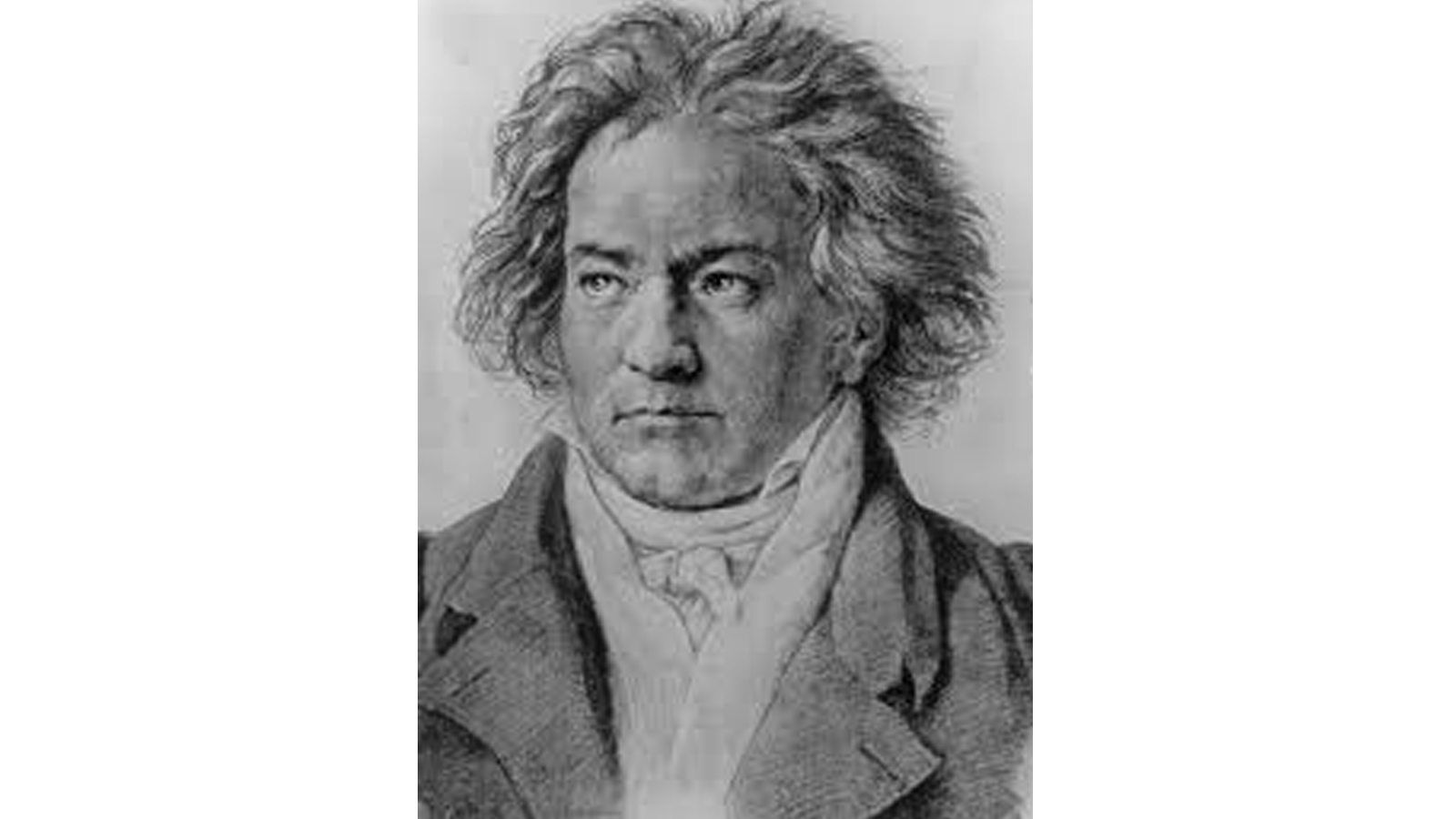

Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A

To those listeners who first heard it, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 was a stunner, and it still affects people who hear it for the first time in the same way. It is the culmination of what Beethoven was trying to do with his Second and Fourth Symphonies. Beethoven sought to create a symphony that builds on and surpasses the classical model as established by Haydn.

By giving his 3rd Symphony the subtitle, “Eroica” or “Heroic” Beethoven gave each of the four movements a place in the narrative of “a hero,” and, further, he gave the whole symphony an affective or emotional character. His Fifth Symphony was revolutionary too; from the very first, famous notes everything moved toward the end of the symphony; the tension never let up until the coda of the last movement that became an extended, brilliant set of variations on the C major chord. Not a note or phrase was wasted or peripheral, each added its weight toward the final resolution. The Sixth Symphony, subtitled “Pastoral,” was an out and out narrative, a scenic or meditative exercise that unrolled a series of events, engaging the listener’s imagination and memory.

The Seventh Symphony returns to the ideal of the symphony that Haydn developed and brought to its peak in the “London” Symphonies. While each movement of the Haydn Symphony has its place in the affective “narrative” of the whole symphony: a hefty, intellectually challenging first movement, a slow movement that serves as a meditative breather, then a dance movement to re-engage the listener physically and last, a quick, usually light hearted, even breathless, final movement, each movement has its own musical identity with a unique rhythm and melodic profile. What binds the symphony movements together is the overall key structure and the listener’s expectations. Because a contemporary audience “understood” the Haydn model, Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony enjoyed immediate popularity. At the premier in 1814, the second movement, the Allegretto had to be repeated on its own. An unthinkable thing to do with the 3rd, 5th of 6th Symphonies. And it did not just happen once. When the Seventh Symphony was first played in Paris, Berlioz was there, and he reported that the Parisian audience demanded that the Allegretto be repeated.

What separates Beethoven’s Seventh from Haydn’s great symphonies, is the degree to which, even as he made each movement a separate entity, he sought ways beyond simply using the key structure to pull them together. He used variations of the same rhythmic patterns throughout the movements and the same melodic patterns too, like cells built from the same DNA, keep turning up. So the listener is never in any doubt that the notes, in whichever movement they happen to fall, belong to the symphony as a whole. It’s as though Beethoven, who habitually read and raged about the critical commentary on his symphonies, finally said to himself, “I’m tired of having Mozart and Haydn thrown in my face… you jackals (his favorite description of his critics) want a symphony you can understand, here it is!” The symphony has been a crowd pleaser and a critics’ delight ever since.

Top 40 Countdown

A few years ago the listeners to WNED Classical told us what they thought a TOP 40 list of Classical pieces should be. Six hundred and twenty-two different pieces were put forward, and over nine hundred listeners participated. The result, The WNED Classical Top 40, was both startling and comforting. There were a number of surprises, Stravinsky and Copland made the list; Mendelssohn and Schumann did not! It was comforting to know that the two most popular composers were Beethoven and J.S. Bach. The biggest surprise of all was the piece that crowned the list as No. 1.