No. 25

Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor

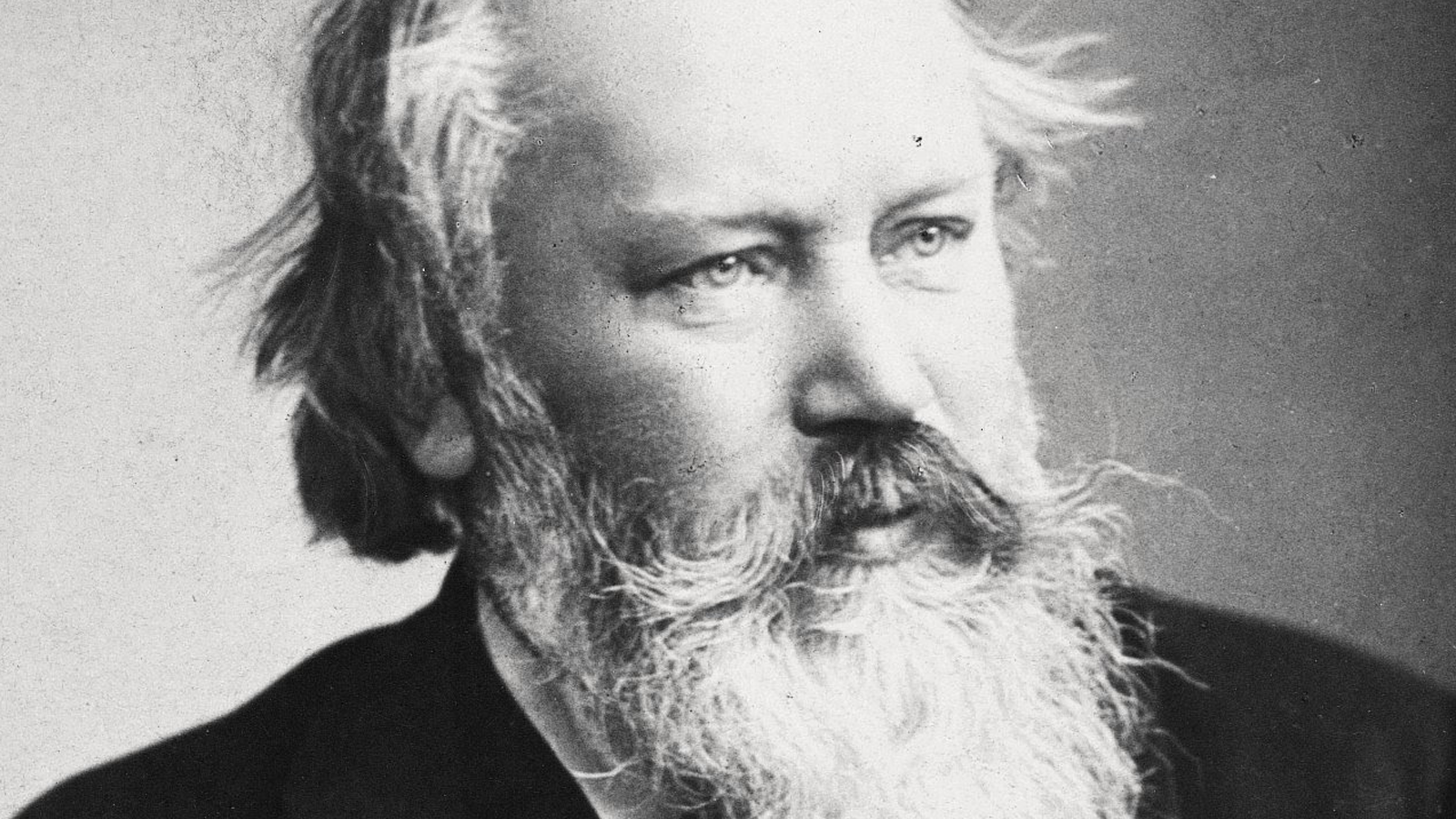

Less than a year after he met the baby-faced blonde pianist-composer, Robert Schumann, declared the young man to be the savior of music, the true heir of Beethoven. That handsome lad was Johannes Brahms.

Schumann had foreseen, following the deaths of Mendelssohn and Chopin, a turn away from the genres and “absolute” music of the classical period best exemplified by Beethoven’s symphonies and concertos, sonatas and quartets. Music was an art form that made its own demands upon a listener without reference to the mundane world or the affairs of men. Music in its purist forms became the advocate for an ideal world. Already, however, a group of musicians who sought ever larger audiences for their work, and who favored music that offered immediate sensational pleasure over intellectual or formal rigor, were already making a case for a music “of the Future”. Leading the vanguard of this party of the Future were Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. Wagner had already written that after Beethoven the symphony was finished. Wagner condemned the symphonies by Mendelssohn and Schumann as pale ghosts of Beethoven’s glory. The Future, in Wagner’s vision, (borrowed in large part from Liszt) meant a conjoining of the Arts, the melding of literature, visual arts and music into a single art form. Schumann still clung to the notion that music itself served society best as an independent art.

Enter Brahms who immediately, thanks to Robert Schumann, became the poster boy for “absolute” music: the symphony, the sonata, the quartet and the concerto. From that moment on, musicians and music followers expected Brahms to write a symphony, and not just any symphony, but a symphony worthy of Beethoven. He dutifully started making sketches for just such a symphony in 1854 which turned out to be, years later, the Piano Concerto No. 1. The next year, in 1855, he started another symphony. Twenty one years later he finished it, his Symphony No. 1 in C minor.

By 1862, Brahms informed Clara Schumann, by then Robert Schumann’s widow, that he was closing in on finishing his symphony. He told his friend Joseph Joachim the same thing, but nothing more was said until 1868. Brahms wrote Clara that he had heard an alphorn while on vacation and that the sound had possessed him and it had put him back in touch with his symphony. Yet not another word until in 1873, when Brahms announced that he had finished an orchestral work, a set of Variations on a theme by Haydn. He was to conduct the premiere with the Vienna Philharmonic. If it was greeted with applause he might bring himself to tackle the symphony. The “Haydn” Variations were favorably received, and in congratulating Brahms, Clara wrote pointedly that the music was worthy of Beethoven. The message was not lost on Brahms; he was still expected to produce that symphony that her long dead husband had promised the world in Brahms’ name. After a concert tour in which the “Haydn” Variations were loudly praised across Europe, Brahms got down to finishing the symphony. The symphony was completed in August of 1876 while Brahms was on vacation in the Austrian Alps, the Alphorn tune that had once possessed him opening the finale. Meanwhile to the north in Bayreuth, Wagner’s Gotterdämmerung, the last of his “Ring” music dramas, made it on stage. So, just when Wagner was to declare the classical symphony buried for good, Johannes Brahms redeemed it.

No sooner did the public hear Brahms 1st Symphony in C minor than it was dubbed “Beethoven’s Tenth”. As Jan Swafford has written: “Yet with all that looming history as a given, the C Minor is one of the most innovative symphonies that the later nineteenth century produced. Once more, and never more powerfully, Brahms achieved a paradoxical resolution of conservative and progressive elements, and did it with a magisterial finality that no symphonist of stature would ever match again.”

Top 40 Countdown

A few years ago the listeners to WNED Classical told us what they thought a TOP 40 list of Classical pieces should be. Six hundred and twenty-two different pieces were put forward, and over nine hundred listeners participated. The result, The WNED Classical Top 40, was both startling and comforting. There were a number of surprises, Stravinsky and Copland made the list; Mendelssohn and Schumann did not! It was comforting to know that the two most popular composers were Beethoven and J.S. Bach. The biggest surprise of all was the piece that crowned the list as No. 1.