No. 27

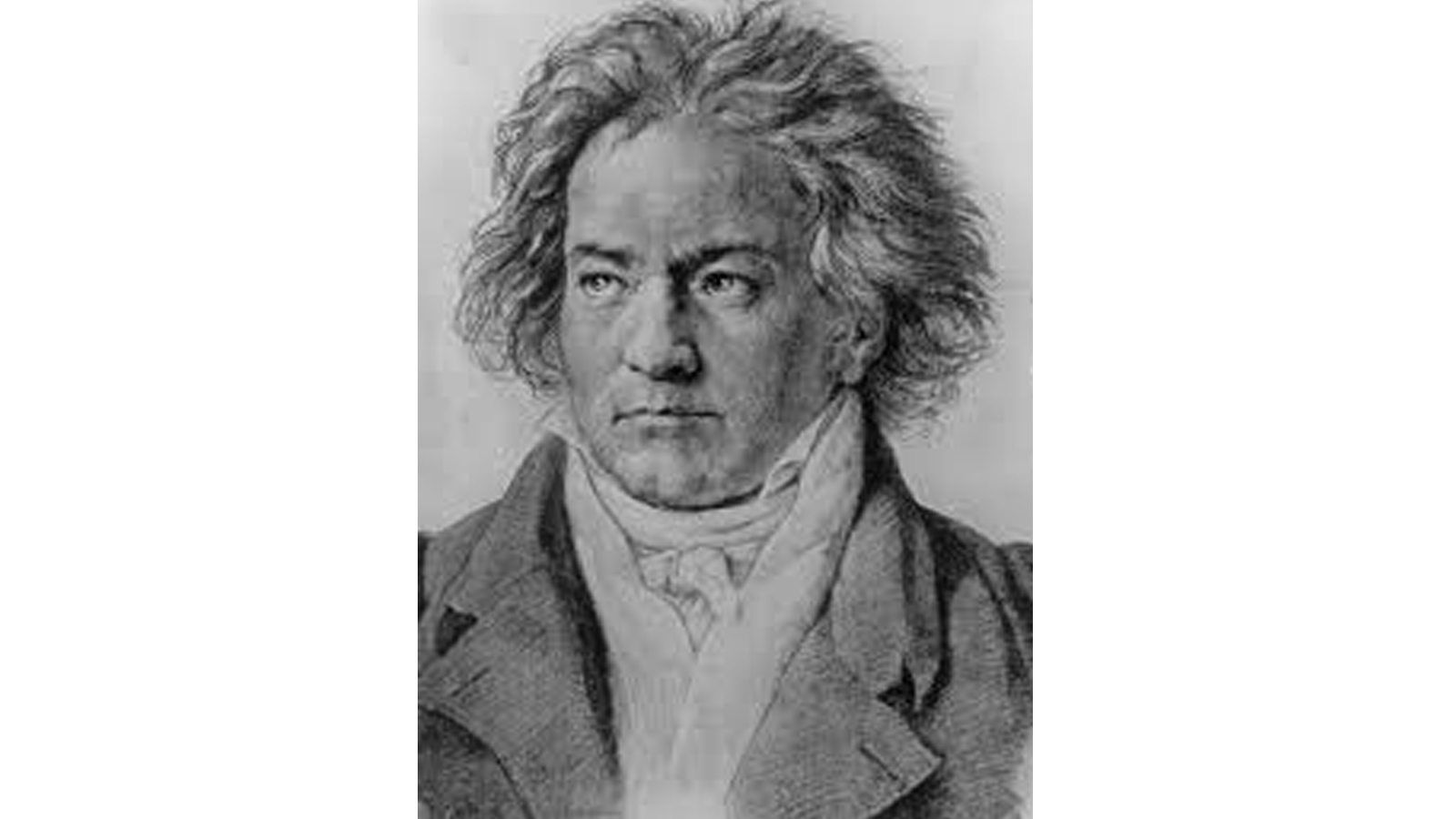

Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D

Beethoven wrote his only Violin Concerto at the end of a period of intense creativity under a deadline. The year was 1806, a short, alas, period of peace in the middle of the Napoleonic wars, and in the last six months of that year, Beethoven composed the three strings quartets for Count Razumovsky; the Symphony No. 4, the second and third Leonore Overtures, revised Fidelio and in a rush, his Violin Concerto. That’s because the Concerto was to be played in one of his monster concerts put on to benefit himself. The man who had agreed to play the Concerto was Franz Clement, who was a home grown prodigy. Clement did not pursue a touring career, but spent his time as the leading violinist in the city of Vienna. Beethoven knew Clement and liked him. On the manuscript Beethoven wrote “Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement”; “Concerto for clemency from Clement”.

Still, having a friend on hand to play the Concerto caused the composer a number of problems. Clement was an old fashioned violinist. From about the 1780s, violin playing had been revolutionized by a new kind of bow, invented by a Frenchman, the “Torte” bow, favored by the most famous of violin virtuosos at the time, Giovanni Viotti. Other improvements had also been made. Many a beloved Strad was overhauled (indeed, all the strads still being played today have been modified); the fingerboards were extended and strengthened, the sound posts thickened and the bridges raised. This led to much showier and louder playing with a great deal of lightning string crossings and multiple chording (“double stopping”) by a whole new crop of violinists. In 1802, Beethoven had already written a Violin Sonata for one of those new virtuosos, Rudolf Kreutzer, a sonata that employed almost every innovation that could be conceived that would show off these newest techniques of violin playing. But such showmanship was beyond Clement. He didn’t use a “Torte” bow, nor had his violin been modified. His one unique gift was his ability to stay in tune no matter how high the notes went. Writing at white heat, Beethoven was ever mindful of Clement’s limitations and his strengths. Because of that, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is unlike almost every other concerto written for the instrument up to that time.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is primarily lyrical. It bears little of his usual drama; no heaven storming here, except the violin writing is stratospheric. The violin seems much of the time to be hovering high above the orchestra, ethereal, angelic. The final rondo is probably based on a tune by Clement himself gussied up by Beethoven because he had only a day to finish. Yet for all its hunting horn clichés the final rondo remains infectious, joyful and light hearten. Clement himself didn’t think the Concerto set him off to best advantage so interpolated his standard party trick in the middle. He played a tune on just one string while holding the violin upside down! After a bow or two, Clemant calmly finished Beethoven’s Concerto. Praise fell on the Fourth Symphony and even more on the Fourth Piano Concerto, but critics were generally puzzled by the Concerto. Needless to say it took a generation before Beethoven’s Concerto made it into the repertory. Paganini never touched it. It was violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms’ friend, who, by his advocacy made Beethoven’s Violin Concerto one of the essential pieces in the western musical canon.

Top 40 Countdown

A few years ago the listeners to WNED Classical told us what they thought a TOP 40 list of Classical pieces should be. Six hundred and twenty-two different pieces were put forward, and over nine hundred listeners participated. The result, The WNED Classical Top 40, was both startling and comforting. There were a number of surprises, Stravinsky and Copland made the list; Mendelssohn and Schumann did not! It was comforting to know that the two most popular composers were Beethoven and J.S. Bach. The biggest surprise of all was the piece that crowned the list as No. 1.