No. 34

Saint-Saëns: Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Organ

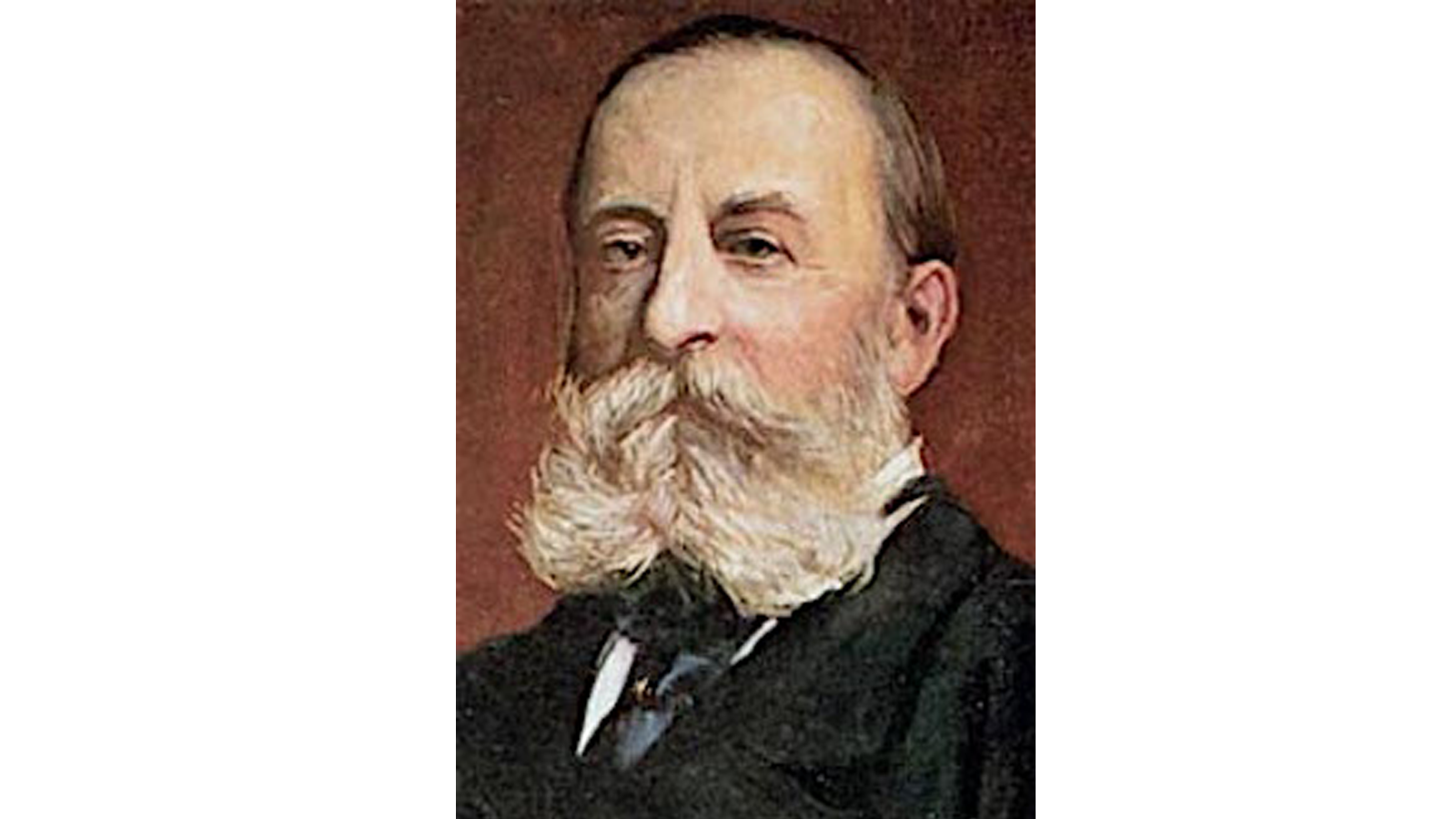

At age ten, seated at a keyboard, young Camille Saint-Saëns would offer to play any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory. The only other pianist in the world at the time who could match that feat of memory and keyboard technique was Franz Liszt. And ever after these two musical giants, Beethoven and Liszt, would guide Saint-Saëns career and musical thinking. And when, 40 years later, London’s Philharmonic Society commissioned him to write a musical work --just as they had commissioned Beethoven-- Saint-Saëns responded with a Symphony that paid homage to both Beethoven and Liszt.

Although quickly recognized as a genius, Saint-Saëns musical bent did not immediately make him popular. Like his idols his early renown was as a keyboard player, not as a composer. Graduating from the Paris Conservatoire, he became a church organist. When Liszt heard him he immediately declared him the best organist in the world. Even as he moved from small churches to take his place at the great organs in the cathedrals of Paris, he was busy composing.

But publishers weren’t interested in his first two Symphonies. He did manage to get a Symphony published when he was twenty, a symphony in F nicknamed “Urbs Roma,” “The City of Rome”. It went unnoticed. Parisians were captives of the opera; whether grand, lyric or light, they loved vocal music above all else. Saint-Saëns wasn’t interested in being a Thomas, a Gounod, or even an Offenbach; he wanted to emulate Beethoven. Berlioz, who understood better than anyone else the dilemmas Saint-Saëns faced, said of him, “He knows everything, but lacks inexperience.” Saint-Saëns was just too good for his time and his countrymen. As his fame grew, so did some appreciation for his earlier efforts. A symphony he had written at age twenty three was finally published as his Symphony No. 2 in 1878, when Saint-Saëns was forty-two years old. But it was only published after Paris was introduced to the only opera Saint-Saëns ever wrote that has maintained its place in opera houses around the world, Samson and Delilah. Incidentally, no Parisian impresario was interested in the opera because it portrayed a Bible story until Liszt produced the opera in Weimar where it was deemed positively scandalous. Only then did every impresario in Paris clamor for the honor of producing it. In Paris scandal has always paid.

So upon receiving the commission from London’s Philharmonic Society for a musical work, Saint-Saëns decided immediately that the piece should be a symphony, a symphony that pays homage to Beethoven and Liszt. Saint-Saëns favorite Beethoven Symphony was the Fifth with its stirring journey from C minor to a triumphant C major. So Saint Saëns decided to model his own fifth symphony after Beethoven’s which would begin in C minor and end triumphantly in C major. And though the Saint-Saëns Symphony is officially divided into two parts; that only hides the same four movement structure and sequence as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Yes, we know the Symphony as the Symphony No. 3, but Saint-Saëns knew it to be really his fifth symphony, he, at least, never forgot his first two unpublished symphonies.

The one piece of Liszt’s that Saint-Saëns often played was Totentanz, or “The Dance of Death” which used as its starting theme the old plain chant for the dead, Dies Irae . The first theme of Saint Saëns Symphony is also derived from the Dies Irae plain chant. Over the course of the symphony we often hear that Dies Irae theme in new guises as Saint-Saëns uses a method pioneered by Liszt that the older composer called “Thematic Transformation”. The last time the Dies Irae theme is heard is as a triumphal chorale in the climax of the final movement. Saint Saëns dedicated the Symphony to the aged Liszt who only had a few more months to live. The homage to Liszt also came in the form of adding three keyboards to the orchestration, the most famous of which is the organ that quietly steals into the symphony at the start of the second movement, the andante and then reappears, bursting with thundering glory, for the finale. Because of that the Symphony has been nicknamed “the Organ,” but Saint-Saëns was a bit more precise, he always used the term “with organ”. The other two keyboards are pianos; it was the first time a piano, let alone two of them had ever been used in a symphony.

The premiere in London’s St. James Hall with the Prince of Wales in attendance was, Saint Saëns would often say, “The very top of his career.”

Top 40 Countdown

A few years ago the listeners to WNED Classical told us what they thought a TOP 40 list of Classical pieces should be. Six hundred and twenty-two different pieces were put forward, and over nine hundred listeners participated. The result, The WNED Classical Top 40, was both startling and comforting. There were a number of surprises, Stravinsky and Copland made the list; Mendelssohn and Schumann did not! It was comforting to know that the two most popular composers were Beethoven and J.S. Bach. The biggest surprise of all was the piece that crowned the list as No. 1.