Evolution of the Richardson Olmsted Campus

It took decades to build. It endured decades of neglect. But in the hands of a community dedicated to preserving it, the Richardson Olmsted Campus is being reimagined.

Long Corridor

Among other innovations, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride’s plan for mental asylums called for long, tall corridors called dayrooms. These dayrooms, where patients were meant to spend their days, were designed to ensure maximum light and air – they featured tall ceilings, huge windows, and a modern circulation system that could pump heated or fresh air into the halls. The spaces were filled with diverting activities for patients and featured covered porches off one side.

Given the central importance of the dayroom to the Kirkbride Plan, the preservation of these 210’-long hallways was considered mandatory for the reuse of the Richardson Olmsted Campus. This proved challenging as there are not many modern-day uses that call for the wide corridors Dr. Kirkbride found so crucial. But the Richardson persevered and found a new use that preserved the dayroom corridor – a hotel, with hotel rooms where patient rooms once were and the dayrooms used for programming and events.

Connector

_1280X720.jpg)

Connecting each wing building at the Richardson Olmsted Campus to the next – and stepping them back a full building’s depth – are the curved connector corridors. These curved spaces were an innovation of the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane.

While Dr. Kirkbride’s original plan did recommend stepping the buildings back from each other, the Kirkbride Plan didn’t have connector hallways at all; it simply attached the wing buildings to each other with no hallway between. As the plan became more widely used and adapted, connector hallways that jutted out at right angles from the buildings became more common.

This sort of angled connector was used at the New York State Asylum at Utica, under Superintendent Dr. John Gray. Dr. Gray was invited to advise on the new asylum to be built on Buffalo. One of his first recommendations was to make sure the connectors were curved, not angled. Why? Because he knew first-hand how overcrowded a state hospital could become and how easy it was to fit extra beds in a connector with straight walls, even though it was a far from ideal place for a patient to live. To avoid that temptation, Dr. Gray recommended curved connectors at the Buffalo State Hospital. His advice was taken and the beautiful curved connectors, with Minton Tile floors imported from England, were introduced at the Buffalo State Asylum. They remain a beautiful part of the Richardson to this day.

The North Entry

In the 1920s, a boxy, brick addition was added to the Buffalo State Hospital’s northern side. It would remain there for decades, marring the original H.H. Richardson design of the Towers Building. When the time came to reuse the buildings, it was decided that the addition would be taken away and replaced with a modern entry to the new hotel and architecture center.

The new entry is ADA accessible and the glass showcases the Richardsonian Romanesque sandstone in a way the brick addition couldn’t. Feedback from the community during the reuse process refined the design to make sure the space acted as a jewel box, showing off as much of the original exterior as possible. Today, visitors can view the original Medina sandstone exterior, complete with Richardsonian red mortar, year-round.

The Chapel / The Ballroom

While the iconic towers of the Richardson Olmsted Campus are purely decorative, the room located between them has always been a busy space. The large, airy room was originally built to serve as nondenominational chapel for the former Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. Eventually, a new chapel was built on the grounds that was more accessible and the fourth floor room was reborn as a multi-purpose space. Patients put on theatrical performances as part of their treatment and learned new handicrafts like basket-weaving, all in the airy room between the towers.

When the Richardson Olmsted Campus was rehabilitating the space, it was decided to maintain the mixed-use history of the room and create a massive ballroom for events as part of the new hotel. These days, you’re equally likely to encounter a wedding reception, a conference, a massive yoga class, or a special brunch happening in the former chapel.

Grand Staircase / Administration Offices

The Towers Building was built to house the Administration of the former Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. The first floor was all offices and, when patients first arrived at the hospital, this is where they would first meet with their doctors. The second floor of the building was home to the hospital superintendent and his family and the third floor housed the remaining medical staff. Traveling between the floors involved walking up and down a large, grand staircase made of hardwood and decorative carvings. When more space was needed to house patients in the early twentieth century, the medical staff moved out to separate buildings on-site and the second and third floors were turned into female patient housing.

When originally built, the grand staircase ending on the first floor of the Towers Building was centered with two staircases from the second floor meeting in the middle and coming down to the first floor. This configuration took up most of the floor space of the first floor hallway and provided inefficient. In the 1920s, the staircase was dramatically reconfigured. One third of the grand staircase’s width was removed and the entire staircase was moved from the center to the side of the hallway.

This new arrangement fit nicely with the upstairs rearranging that had already been done to accommodate patient housing, instead of medical staff housing. Now, the staircase would no longer run directly from the third floor and out the front door on the first – instead, the stairs were more segmented and cut down on the free flow of people between floors.

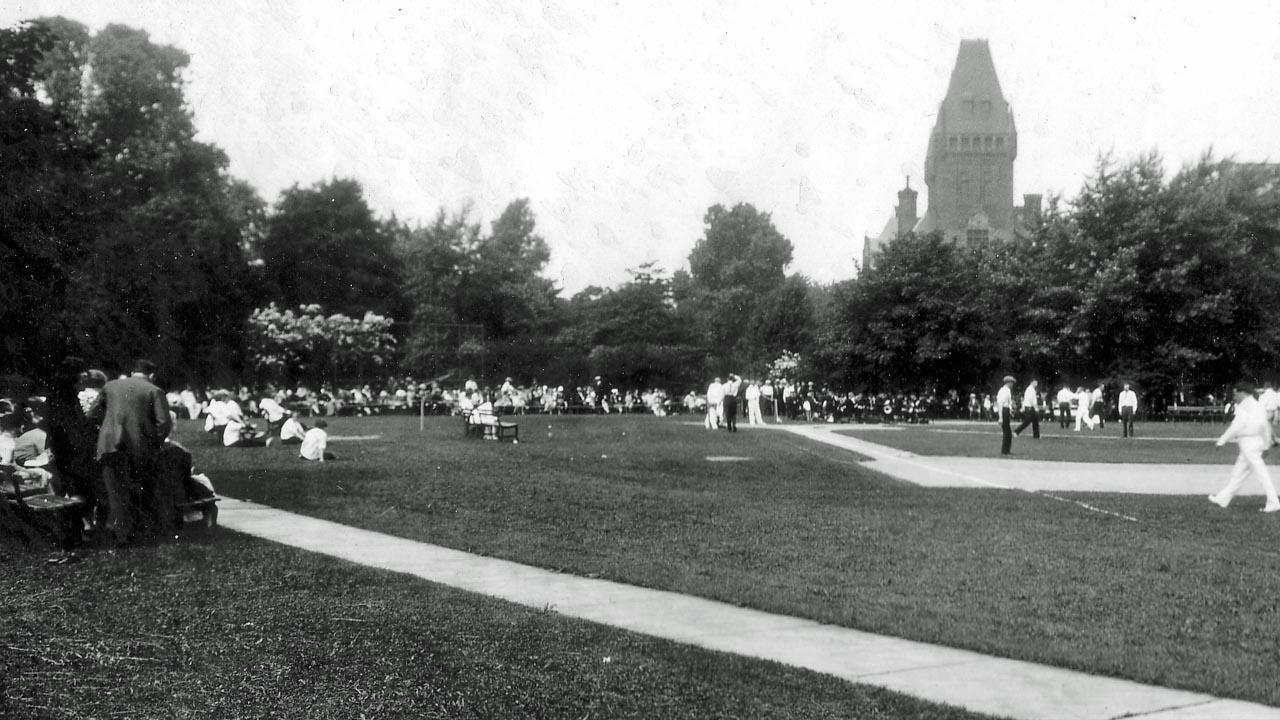

South Lawn

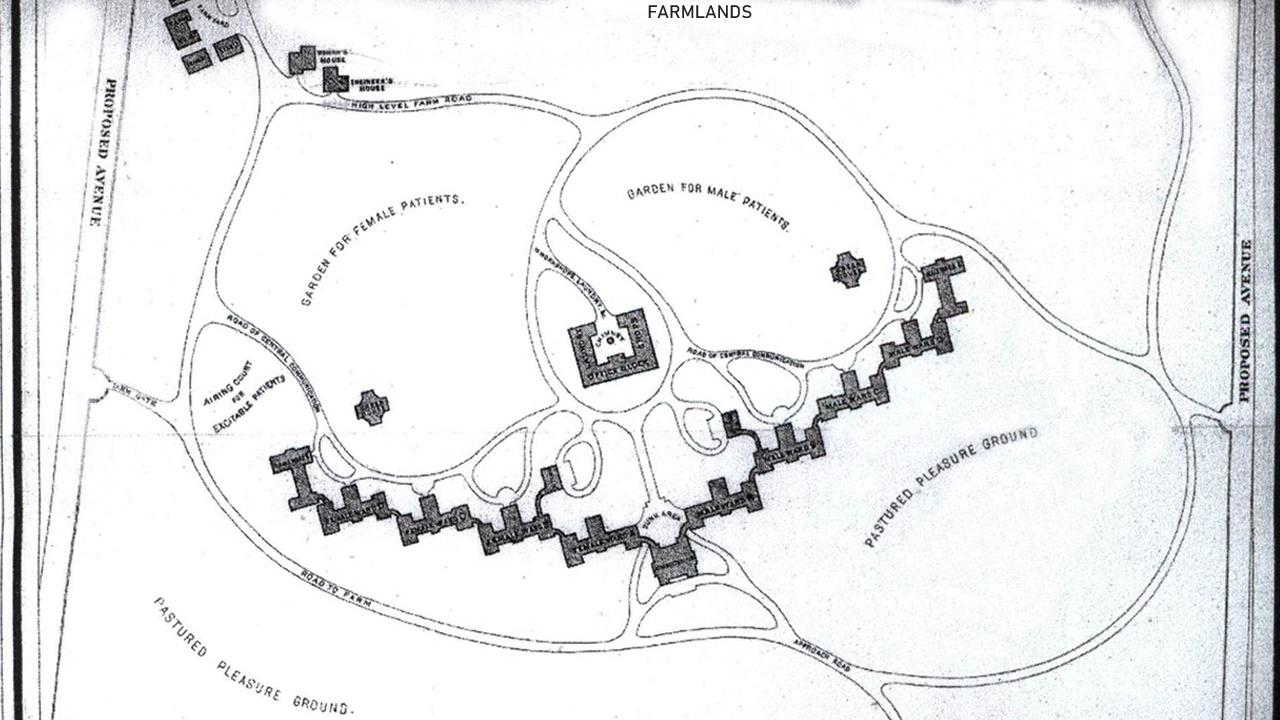

The former Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane lived on 203 acres of parkland when it was first built in the 1870s. Today, 42 acres of that original campus remains, with the most prominent greenspace in the front of the Towers Building: the South Lawn. Originally, the South Lawn was part of a larger park plan designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Olmsted and Vaux created their plan for “pleasure grounds” around the hospital to include a pond, a baseball diamond, and curving walkways for patients to stroll.

But by the mid-twentieth century, Olmsted and Vaux’s original vision had been lost – a parking lot covered much of the greenspace on front of the Towers Building and 100 acres of land had been appropriated to create Buffalo State College’s campus.

The Richardson Olmsted Campus set out to restore the landscape with a new plan inspired by Olmsted and Vaux’s original design. With the site off-limits to the public for centuries, it was critically important that the landscape renewal welcomed the community on-site and created a public park-like atmosphere that everyone could enjoy.

Today’s “Olmstedian” South Lawn greenspace features a great lawn inspired by Olmsted’s work on Central Park in New York, curvilinear pathways, and rain gardens, a modern and eco-friendly touch. The old parking lot itself was even reused – ground up and made into gravel, the parking lot now serves as the surface of the new pathways around the greenspace.

Buffalo Psychiatric Center

Buffalo Psychiatric Center

Buffalo Psychiatric Center

Buffalo Psychiatric Center

Buffalo & Erie County Public Library

Joe Cascio

Joe Cascio

Joe Cascio

Paul Pasquarello

Paul Pasquarello

Paul Pasquarello

Reimagining a Buffalo Landmark is funded by the Peter C. Cornell Trust, The Zemsky Family and the Members of Buffalo Toronto Public Media.