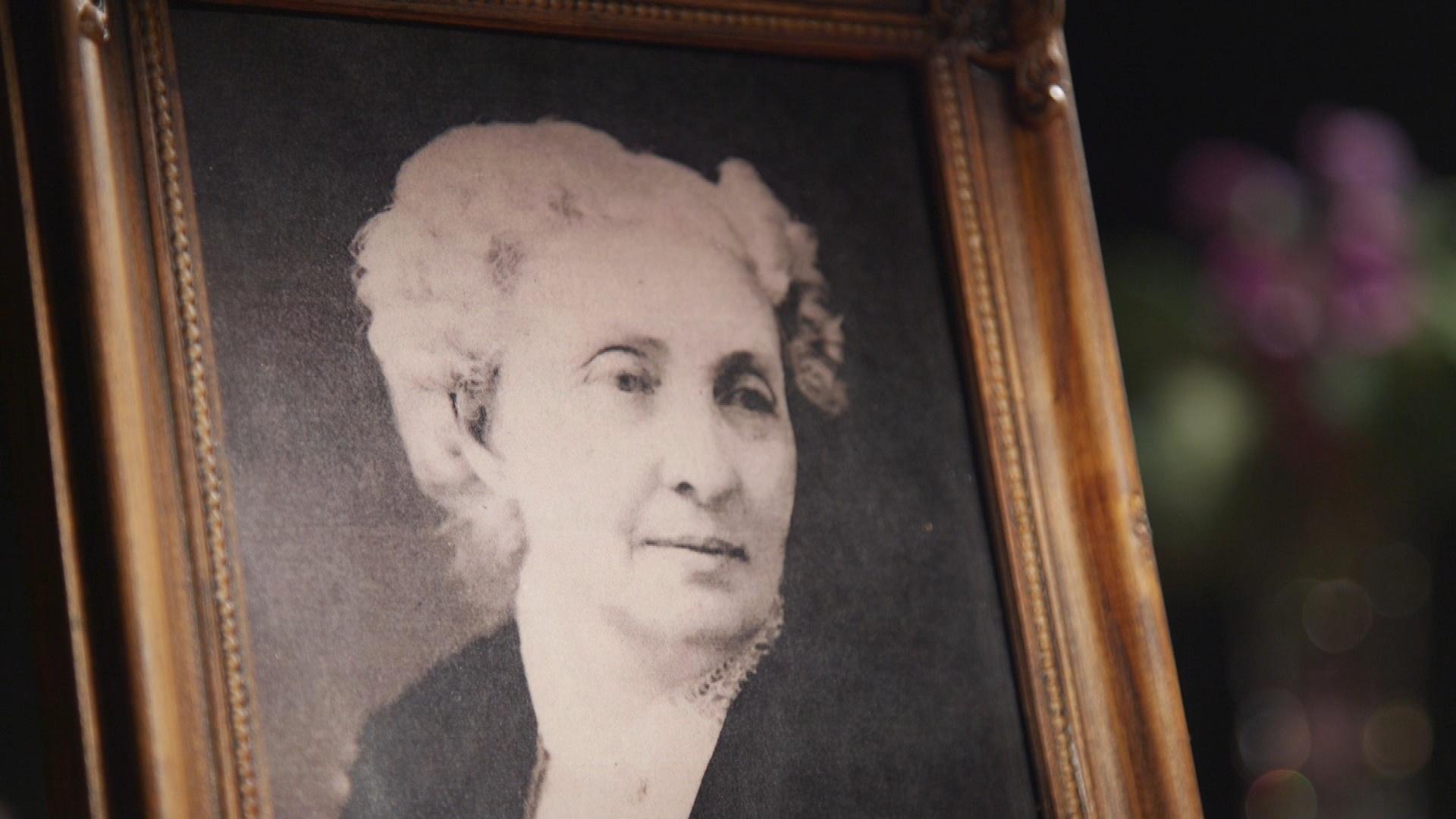

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

Born August 7, 1813

Died August 24, 1876

“I think what's important about Paulina Wright Davis and women of her time is that she and many others believed that women added something new and important to the polity. Most people were uncomfortable with women asking for the right to anything, and you see that reflected in newspapers at the time. So Paulina Wright Davis decides to take things into her own hands and start her own publication devoted to women's rights.”

— Dr. Susan Goodier, Associate Professor of History, SUNY Oneonta

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis was a forerunner of women’s rights, strategizing with the likes of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Ernestine Rose long before the first women’s rights convention to pass the Married Women’s Property Act in New York. She saw incremental successes as vital to the long-range goal of suffrage — and ultimately, equality. She would use her social privilege and wealth to launch the first publication dedicated to women’s rights, and her writings would ultimately become one of the most complete records we have about the early days of the movement.

In 1813, Western New York was swept up in the fervor of religious revival. Known as the Second Great Awakening, this period birthed a new passion for social movements like temperance and abolition. It was into this scene that Paulina Kellogg was born. Orphaned at only 7 years old, Paulina was sent to live with her strict aunt in Le Roy, NY.

Under her aunt’s influence, Paulina embraced the church. When she expressed interest in becoming a missionary, church leadership told her that was something unmarried women couldn’t do. That didn’t sit well with a young Paulina Kellogg. She later recalled that she was not happy until, “I outgrew my early religious faith, and felt free to think and act from my own convictions.”

Those convictions quickly became political. Building on experience she gained through abolition work with her first husband Francis Wright, Paulina Kellogg Wright started agitating for women’s property rights with suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Ernestine Rose.

At the time, married women had no control over their personal property and real estate. Anything a woman owned was considered to be her husband’s property. After more than 10 years of relentless pressure from Wright and other activists, the New York legislature finally passed the Married Women’s Property Act in 1848 — the same year as the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention. New York’s law became a model for other states to follow.

Paulina Kellogg Wright became a widow after just 12 years of marriage, leaving her wealthy and independent. She relocated to New York City and began to study medicine — not to become a physician, but to teach other women about their bodies. For several years, Davis traveled the eastern United States with a mannequin imported from France and lectured women on anatomy and physiology. The topic of women’s bodies was so taboo that some women reportedly fainted during the lectures.

After a few years of her lecture circuit, Wright married Rhode Island politician Thomas Davis. Paulina Wright Davis moved to Rhode Island to be with her new husband and got involved in New England suffrage work. By 1850, Davis found herself organizing the first National Woman's Rights Convention in Worcester, MA.

The convention was not popular with the press. The New York Herald, for instance, attacked the speakers’ appearances and portrayed the attendees' demands as ridiculous, framing the convention in their headlines as an “awful combination of socialism, abolitionism, and infidelity.”

As far as the media was concerned, women’s roles were purely domestic. The only women’s media available at the time focused on housekeeping and motherhood. After the convention, Davis had a newfound understanding of the power of media — and she was determined to use it for the cause. She launched The Una, a magazine devoted to the “elevation of woman.” The Una covered suffrage, and other issues of women’s equality in labor, marriage, job opportunities, and pay. It was widely read and discussed among suffragists.

Having successfully launched The Una, Davis turned her attention to another project dear to her heart: recording the history of the suffrage movement. In 1870, she managed to juggle organizing the National Woman Suffrage Association’s convention in New York City AND writing a history of the first 20 years of the women's suffrage movement. Her meticulous A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement is one of the most complete records of the movement’s early years. Davis knew when it was published in 1871 that the finish line was nowhere in sight — but she could not have predicted that work would continue for another 40 years.

As far as the media was concerned, women’s roles were purely domestic. The only women’s media available at the time focused on housekeeping and motherhood. After the convention, Davis had a newfound understanding of the power of media — and she was determined to use it for the cause. She launched The Una, a magazine devoted to the “elevation of woman.” The Una covered suffrage, and other issues of women’s equality in labor, marriage, job opportunities, and pay. It was widely read and discussed among suffragists.

Having successfully launched The Una, Davis turned her attention to another project dear to her heart: recording the history of the suffrage movement. In 1870, she managed to juggle organizing the National Woman Suffrage Association’s convention in New York City AND writing a history of the first 20 years of the women's suffrage movement. Her meticulous A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement is one of the most complete records of the movement’s early years. Davis knew when it was published in 1871 that the finish line was nowhere in sight — but she could not have predicted that work would continue for another 40 years.

Reflecting on the need to finish the fight, she wrote:

“The reform which we propose. . . is radical and universal. . . The emancipation of a class, the reform of half the world”

-Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

Major support for Discovering New York Suffrage Stories was provided by The National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the Human Endeavor, by the Susan Howarth Foundation, and KeyBank in partnership with First Niagara Foundation. With additional funding from the Fred L. Emerson Foundation and Humanities New York.