Matilda Joslyn Gage

Born March 24, 1826

Died March 18, 1898

“Matilda Joslyn Gage called for an end to patriarchy. And she didn't just do it once. For her, the fight for women’s rights was a revolution that would result in a regenerated world. Were she alive today, Matilda Joslyn Gage would still be working for that regenerated world.”

— Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner, Executive Director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

Suffrage was a radical idea, but Matilda Joslyn Gage saw it as the first step on the way to liberty and full women’s equality, as modeled by the Haudenosaunee culture.

She worked right alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony as they fought for women’s rights. Together they led the National Woman Suffrage Association and edited the first three volumes of the definitive history: the History of Woman Suffrage. So why haven’t we heard of Gage or her contributions?

Gage was born in 1826 in Cicero, NY, just 50 miles east of Seneca Falls on the shores of Lake Oneida. Her father taught her subjects usually reserved for boys, like anatomy and physiology. Perched along the Erie Canal, her home was a station on the Underground Railroad and a gathering place for radical reformers organizing around the burning social justice issues of the day. Gage attended anti-slavery protests regularly and circulated anti-slavery petitions in her childhood. This upbringing made Gage not only a critical thinker, but shaped her as a political radical.

Gage was pregnant with one of her five children when the women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls occurred, so she stayed home. She finally got involved in the suffrage movement with a speech at the third national Women’s Rights Convention in Syracuse in 1852. Despite her young age and quiet voice, Gage’s words were forceful:

“Although our country makes great professions in regard to general liberty, yet the right to particular liberty, natural equality, and personal independence of two great portions of this country is treated ... with the greatest contempt; and color in the one instance, and sex in the other, are brought as reasons why they should be so derided; and the mere mention of such natural rights is frowned upon, as tending to promote sedition and anarchy.”

In the audience was none other than Susan B. Anthony. The two of them soon found themselves working side by side on suffrage issues.

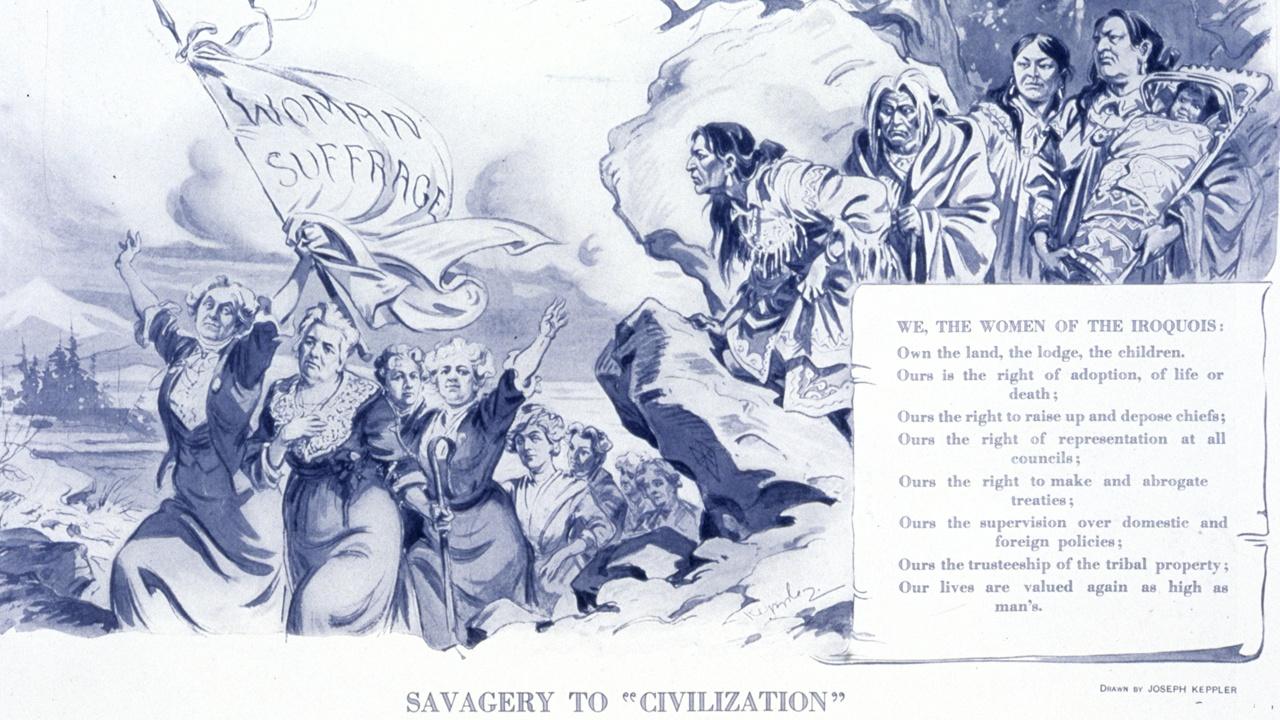

At the same time that Gage was coming into her own as a women’s rights activist, she was developing an interest in her indigenous neighbors, the women of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Also known as the Iroquois or Six Nations, the Confederacy includes the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. In the mid-19th century, New Yorkers were intimately acquainted with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy through individual relationships and local newspaper coverage of their community news, politics, and sports.

Gage felt an incredibly strong connection to the Haudenosaunee philosophy and way of life. While she was president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Gage penned a series of articles on the Haudenosaunee nations of central New York for the New York Evening Post. In describing the culture, Gage wrote, “Never was justice more perfect; never was civilization higher.”

In particular, Gage noted the stark differences between women’s equality in native and European American societies. Haudenosaunee women were respected as equal voices in government. Gage saw this as an ideal example of gender equality and tried to bring suffragists together with Haudenosaunee women as allies. In 1893, she was recognized for this work with an honorary adoption into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk nation and was given the name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi, or “She Who Holds the Sky.”

While Gage was being honorarily adopted into the Wolf Clan, she was being pushed out of the suffrage movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to grow the movement’s numbers by bringing temperance activists into the suffrage fold. Gage vocally opposed their religious conservatism, arguing that connecting voting rights to religious doctrine would threaten the separation of church and state. This feud drove a wedge between these formerly close friends.

Anthony and Stanton began to distance themselves from Gage’s more radical politics. By 1890, Gage had had enough. She left the main suffrage movement and founded the Women’s National Liberal Union, which focused on the pursuit of broader feminist and human rights goals, including reproductive justice and an end to violence against women. As the suffrage movement became more conservative, they quietly wrote the radical Gage out of the annals of their history.

Gage’s work is just now claiming its rightful place in the suffrage conversation. Throughout her life, she always believed suffrage would provide women with a voice through their vote, giving them power to fight for gender equality.

“There is a word sweeter than mother, home or heaven. That word is liberty.”

-Matilda Joslyn Gage

Major support for Discovering New York Suffrage Stories was provided by The National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the Human Endeavor, by the Susan Howarth Foundation, and KeyBank in partnership with First Niagara Foundation. With additional funding from the Fred L. Emerson Foundation and Humanities New York.